My grandfather was a quiet and dignified man. He was principled and loyal, hard-working, intelligent and with a passion for laughter. His whole body would shake when he laughed and if he was trying to suppress a laugh his belly would wobble, an endearing memory that can bring him back to me in an instant. Grandfather, Paddy, had been a prisoner of war (PoW) in the second World War. Like many of those sent to serve he did not share stories of those days, until, one day in the late 1980s when I was telling him about a visiting dignitary to our Civil Service office. This sparked in him a memory from working in the fields of an Italian Count in a PoW detail; he recalled the Count coming to inspect the troops as they worked. There followed a selection of funny stories of his time in the camps or on the run in Italy. In me, it kindled a need to understand more about this incredible man and my family history in general. It’s a hobby I have stopped and started many times over the thirty plus years that followed. Digitisation of records, community online forums, DNA testing and matching have transformed the process; an enduring pass-time and I love it! I have no desire to have the highest count of people in my tree, or to reach back the furthest in history, or to find fame and notoriety. For me, family history is about the stories. For that reason, I have come to accept and treasure the `rabbit holes’ of discovery that I frequently tumble into. This story, of Catherine Ratcliffe-Duncan, a pit brow lass from Billinge in Lancashire, is one such rabbit hole.

But let us start on the main path, with my three times great grandparents James and Ellen Duncan. James and Ellen married on 18th November 1839, the marriage registered at All Saints Church in Wigan. I know that their daughter Jane, my great great grandmother was baptised Catholic, which makes me think it probable that James and Ellen were Catholic. At that time a marriage in a Catholic Church would not be recognised as legal and therefore couples had to marry in Church of England. I have much more research to do on James and Ellen so I will leave this thread, tantalising as it is, here to be picked at later! The registration of the marriage tells us that James was 26 years of age, a bachelor and a Collier. Ellen was 23, a spinster and weaver. Both were from Winstanley. Due to the timing of their marriage and their likely Catholicism, I cannot be certain about how many children they had. The first record of a child is on the 1841 census, a son Richard, born on 15th January 1841 at Gustavus Hillock, Ashton in Makerfield. Other children were Peter (registered as Harry in Wirral in August 1842), Hugh (also registered in Wirral, born on 8th November 1844), Mary (born 18th December 1846, in Billinge), James (born 28th February 1849, and baptised at the local Church of England, St Aidan’s) and finally (my great great grandmother) Jane (born 14th January 1852, as I mentioned earlier baptised Catholic, at Birchley St Mary’s in Billinge).

On 13th June 1854, Ellen died from Phthisis, probably tuberculosis lung, at just 44 years old. The death certificate notes that she had been suffering with the wasting lung condition for nine months. James (43) was left with Jane, 2, James, 5 , Mary, 7, Hugh, 9, Peter, 12 and Richard, 13. Later that same year, 30th October 1854, James married local girl Sarah Lea at Wigan All Saints. Sarah also had a child, James, born 18th October 1844, so just ten years old when she married James Duncan. It’s difficult not to disappear down another rabbit hole here and hard to prove or disprove the details, as there are a few Sarah/Sally Leas, I have so little information to go off, and having children out of wedlock seems a commonality. But, I think our Sarah may have had, and lost in infancy, some five children.

On 29th January 1859 (four years and three months after they married) James dies, aged 48. His death certificate states “dropsy” which I understand to be the term applied to oedema, a fluid retention/ swelling of the body, perhaps due to heart or some other organ failure. There’s no way for me to know where the children go at this point but by the fact that they are mostly with Sarah on the 1861 census, I would say she takes care of them. My heart is so grateful.

I say mostly because I do know that Peter died at just 17 years old on 21st May 1860, his cause of death is stated as consumption, again this is almost certainly tuberculosis lung. His occupation is collier, which may have caused or exacerbated any lung condition. Peter’s burial takes place at St Aidan’s, the Church of England chapel where Sarah has attended. It makes me wonder how difficult it would have been for her to observe the Catholic faith that the children had perhaps been raised in? But how sad for Sarah and scary for the children that Peter should die, so young and so soon after their father died?

Jane’s story I will tell another time and in detail, part of a series that will focus on my great great grandmothers and how I relate to their stories; for now, let’s go down that rabbit hole which starts with her brother James.

To recap the story so far, James lost his mum when he was five years old, his dad when he was nine and his older brother Peter when he was just eleven. He marries at nineteen years old, no doubt wanting to pack as much into his life as soon as he can, who could blame him? So, on the 28th October 1868 he marries Mary Teresa Blackster, she is also nineteen and from Liverpool; at least that’s what the wedding certificate says, again so little to go off and I cannot trace Mary Teresa. Blackster is the name recorded on the marriage certificate but I wonder if her name was Baxter? Mary has listed no father’s details on the marriage certificate. The witnesses at the wedding are James Lea (Sarah’s son) and Elizabeth Hurst, the woman James Lea will marry. On 22nd August 1869 the happy couple are blessed with a daughter who they name Ellen. On the 13th July 1871 they have another daughter, Catherine. On 29th June 1873 they are blessed with a boy who they name James, sadly he dies at just five years old. Another boy is born on 29th November 1878 and they also name him James.

On the 1881 census, the family: James; Mary Teresa; Ellen, 11; Catherine, 9: and James, 2, is living at Holy Fold in Billinge. Living next door to the Duncan’s is the Taylor family, Thomas, Rachel and their children: Margaret, 23; Ann, 18; John, 14; Thomas, 12; and Alice, 8.

On 12th October 1882 James and Mary Teresa have another daughter Theresa. Then tragedy strikes in the following July when Mary Teresa dies at just 34 years old. The death certificate states the cause of death as “Debility 7 days”.

The next step in James’s journey is his marriage to Margaret Taylor, remember her, the 23 year old daughter of his neighbour in 1881? Before we come to their marriage in 1884, let’s fill in a bit of back story on Margaret. She was born on 27th January 1857 to Rachel and Thomas Taylor, a coal miner from Billinge. Margaret was the eldest of their eight children, six girls and two boys, her oldest brother John James is ten years her junior – but we will come back to him! Margaret had a baby boy, Peter, on the 1st May 1882 when she was 25 years old, an illegitimate child. Her second child Rachel was born just sixteen days after her marriage to James. On the 1891 census we find both Peter and Rachel living with Margaret’s parents next door to James and Margaret, who perhaps have enough on their hands at that point with another two children, Thomas born 12 September 1886 and Francis Henry born 16th April 1889.

The next ten years were eventful for our family with the two eldest girls, Ellen and Catherine, making their progress to adulthood. On the 1891 census eldest daughter Ellen is in service and Catherine, at this point 19 years of age, a Pit Brow Woman.

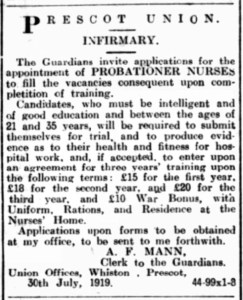

I get the opportunity to wander off into a little social history at this point. Until 1842’s Coal Mines Act, women and children could, and did, work underground at collieries. Apparently, families of the time were none too happy about the regulation of work and loss of earnings to the household, as there were no inspectors until the early 1850s, many ignored the ban. The regulations did not prevent women from working above ground and in Lancashire the women who did so were know as Pit Brow Lasses. They would unload coal from the trolleys, sort it and load it on to wagons. No doubt a tough job, made harder by the emotional pay load of their proximity to the mines when any accident happened.

On 22nd September 1891, Ellen marries James John Taylor, you’ll remember him from next door – he is Margaret’s brother. At this point I guess Ellen can call Margaret her step-mum and her sister-in-law! James and Margaret have a son William born 19 December 1891; and, on 31st December,Ellen and James John have a daughter, Ethel. Catherine is the next to have a child, with Margaret Ann born out of wedlock on 5th March 1893; sadly, Catherine’s baby dies on the 3rdAugust the same year, cause of death being diarrhoea for 7 days. The death certificate for Margaret Ann notes Catherine’s occupation as “labourer at colliery”, her death is reported by James Duncan.

The next year, 1894, Ellen gives birth to a son, Thomas, on 24th March and Margaret has a baby boy, John on August 24th. Sadly, just two days after giving birth to her son, Margaret dies from a pulmonary embolism, and there is further heartbreak when William, aged 2 years and 9 months, dies in October 1894.

Happier news follows the next year (1895) with Catherine marrying Thomas Ratcliffe on 12 Jun and the arrival of their baby girl, Alice on 17th September. Ellen has a baby girl, Margaret Alice, on the 15th July in the following year (1896). Catherine and Thomas have a son, James, born on 11th March 1897, sadly the baby dies on 1st July the same year, the cause of death Tabes Mesenterica, this a form of tuberculosis that destroys the gut and causes wasting.

1898 gets off to a better start with Catherine and Thomas having a baby boy, James, on 19th April but it does not prove any better a year when her father James dies on 30 October 1898. At this point the couple has four children under sixteen:Rachel, 14; Thomas, 12; Frank, 9; and John, 4. I hope to fill the gap of 1899 and 1900 but for now we know that James has made provision for his death and probate is granted to Catherine on 14th November 1898 “to Catherine Ratcliffe (wife of Thomas Ratcliffe) Effects £100” (that’s around £15,000 in today’s money).

Ellen has a son, whom she names James, on 27th June 1899;sadly he dies in January 1901.

Catherine has a daughter, Margaret, on 20th March 1900.

The next record I have (so far) is the 1901 census. Margaret’s parents are living in Dorothy Street, Thatto Heath – they are 69 and 68 years old. Ellen and James John live nearby but collectively they live, what then at least, must have been some distance from Catherine and her family in Billinge. On the 1901 census, Margaret’s son Peter and her daughter (with James?) Rachel, live with her parents. Rachel is something of a riddle as she is listed here with her grandparents, also living with Catherine and Thomas, and at the same time in Pemberton with the family of her future husband Willie under his surname, Ashall.

Also with Catherine and Thomas, are their surviving children Alice, 5, James, 2 and Margaret, 1; as well as her siblings James, 22, Teresa, 19, Thomas, 14, Frank, 11 and John, 6. All in a small stone cottage with a total of three rooms! I am guessing there were some interesting sleeping arrangements.

There follows what seems, from this perspective of free health care, health visitors, immunisations, antibiotics, social careand clean air, a devastating period of loss. I cannot weave a story without unnecessary melancholy, so I will let the bare facts speak for themselves. For Thomas and Catherine it goes like this:

– 2 October 1901 daughter Teresa born;

– 14 April 1903 son William born;

– 16 January 1904 William dies, cause measles;

– 18 March 1905 son Thomas born;

– 24 April 1905 Thomas dies, cause enteritis and convulsions;

– 18 September 1906 son Harold born;

– 16 December 1906 Harold dies, cause debility since birth;

– 13 June 1907, Teresa dies, five years old, cause meningitis;

– 15 August 1908, daughter Lizzie born.

On the 1911, Catherine (39) is living with Thomas (40), her brother John, son James, 12, daughters Margaret, 11 and Lizzie, 2.

In those intervening years her siblings have married, James to Margaret Corday, in 1901; Teresa to James Rimmer in 1901; Rachel to Willie Ashurst in 1905, Thomas to Sarah Ann Nelson in 1906; and Frank to Rachel Roby in 1906.

Catherine has wages coming into the house from Thomas and John, life was surely becoming more settled. On the 11th June 1913 she has another son, Thomas.

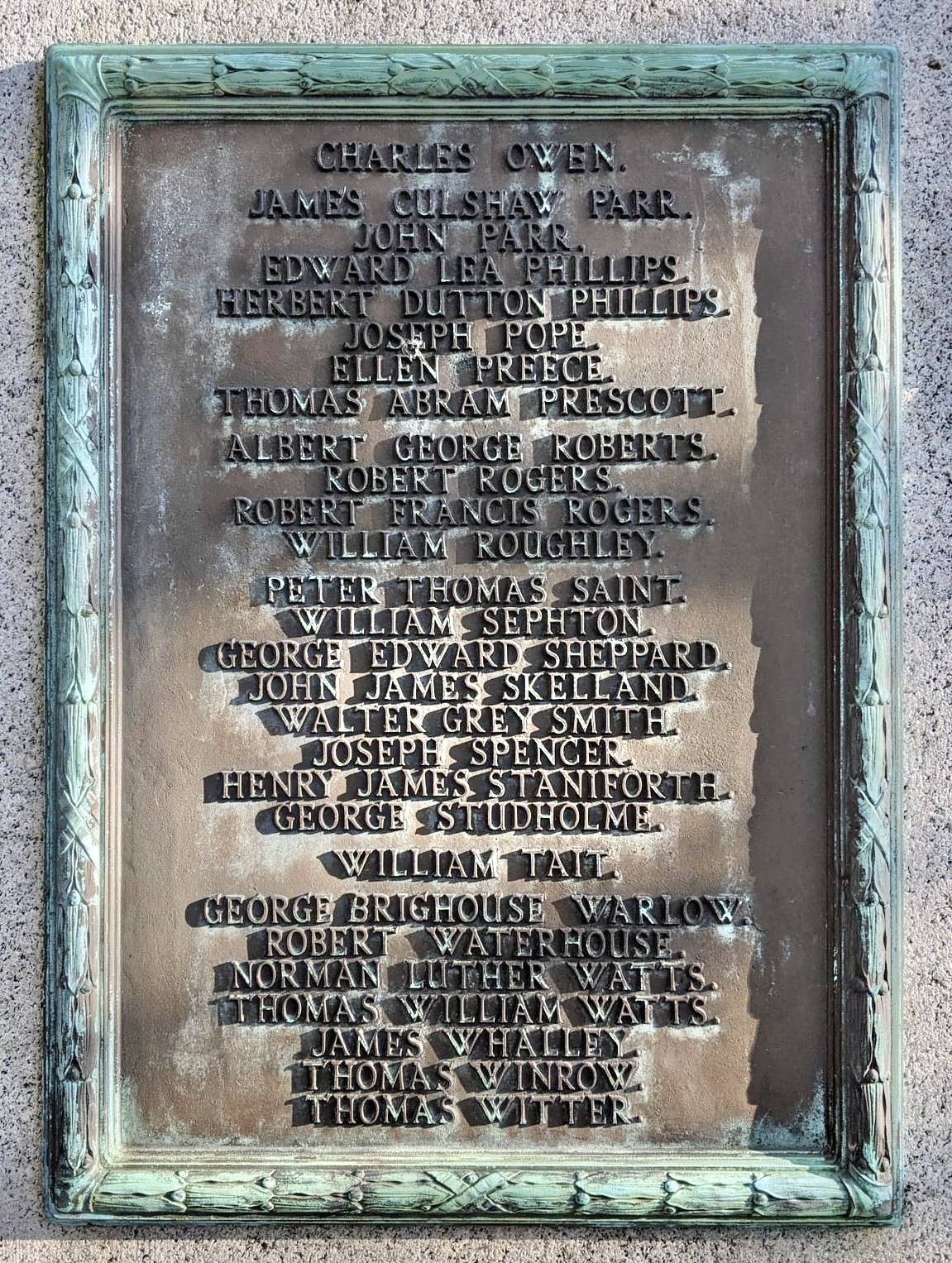

On 25th October 1914 Catherine dies from pneumococcal peritonitis, a primary bacterial infection of the peritoneum (abdominal membrane). Typically associated with use of IUD coils in adult females today. Cleared up by antibiotics which are some way off (Fleming discovered penicillin in 1928) and, of course, would come at a cost until our free health care through the National Health Service began in 1948. So a very sad end for Catherine, my little rabbit hole, my pit brow lass; rest well Cath, your kindness and love shines through all these years later and I hope that your story is heard.